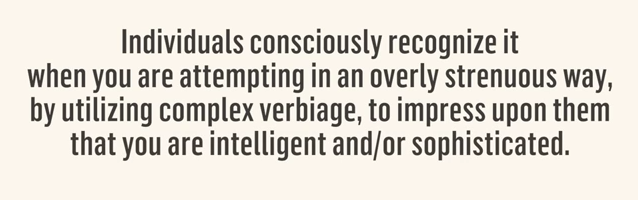

1. Fancy words hide your message

Marie Forleo’s video, 5 Reasons People Don’t Take You Seriously, shows how we get in the way of our message, and what to do about it.

My writer-mind couldn’t help thinking how to use these tips in reverse. Inside a novel, conflict built on miscommunication is quite fun.

Here are Marie Forleo’s tips for clear communication and how to use them backwards in fiction:

Fancy words obscure your message. I hadn’t thought about the way verbal playfulness could be misinterpreted and her example makes it deliciously opaque, I mean, clear:

Shakespeare gives fancy words to characters who don’t understand them. Now I’d like to add a malaprop-prone character to my work-in-progress.

Taking the opposite approach, Dorothy Dunnett’s character, Francis Crawford of Lymond, uses complicated words and obscure Latin quotes as weapons, tools for seduction, or as a dazzling smoke-screen.

Maybe, the more delightful the language is in a story world, the less useful it is for getting your point across in the real world. And vice versa.

2. Lose the "dumb" disclaimer

Instead of offering a “dumb” idea, say: “What about this?” I’ve seen this speech habit associated with women and girls. Imagine a villain who suggests ideas with disclaimers that turn out to be clues.

P.G. Wodehouse’s character Wooster combines “dumb” disclaimers with fancy words in an endearing way. [If you like Wodehouse, you have to read his lovely interview about the art of fiction.

3. The power of AND. . .

Try “Yes, and. . .” instead of “Yeah, but. . .”

I’m not good at this one, and 🙂 I’ve heard it before. My current heroine could get into a lot of trouble with “Yeah, but” and if I gave her this trait, I might learn it myself. I love the idea of a character trying to get a seat at a table, round or otherwise.

“If you haven’t been invited to give feedback and you really want a seat at the table, “Yes, and” will help you get one.” –Marie Forleo

4. Get people intrigued . . .

Instead of blasting people with your ideas, get people intrigued first.

Remembering to breathe is key, both in fiction and in real life. This is also the way to pitch a book idea at a writing conference.

The natural tendency is to blast listeners with everything you know and love about your story, to try to anticipate everything that people would want to know, or to list every detail that could entice them into wanting to know about the story. (Did you fall asleep during that sentence?)

The most powerful way to catch someone’s interest is to tell part of a story. And then shut up.

This is called a “hook.” 🙂

5. Follow-up. Don't apologize and be mousy.

Try language like this:

Good advice to follow for query letters.

“Mousy-ness” is the reverse of the character trait in tip #1. It’s another kind of smoke-screen that says: “Don’t look at me too closely.”

What do you think about Marie Forleo's tips?

What do you think about Marie Forleo’s tips? Do you have favorite fictional characters with confusing speech habits? I’d love to hear about them.

An inventor princess with a public speaking problem . . .

Do you have kids who keep getting overlooked? A zany fairy tale is an enjoyable way to learn how to be heard . . . until the castle catches on fire!