Is Migration Our Lot?

Lately, I’ve been wondering if migration is our natural lot and living peacefully in one place all our lives a rarity. Cranes are migrating and their calls remind me of spring.

The current news shows destroyed cities in Syria, failed cease-fire talks, and a refugee bus being shouted down by people in the former Democratic Republic of Germany.

At my mother-in-law’s birthday party, some friends told how their families fled from the invading Russians, near the end of World War II. One family fled as late as 1945. Here’s my rough translation into English:

What It Was Like to Flee . . .

A knock came at three o’clock in the morning: we had to get out. We fled in a matter of two hours, with only the clothes we had on. The snow was up to the horses’ bellies and my mother packed us into the hay wagon with bedding, so we wouldn’t freeze.

Our father was one of three men assigned to the farm, to keep producing food. Unarmed, they were supposed to stay at the farm to defend the front against the Russians.

The countess, our angel, helped us to get out. She didn’t take any extra luggage for herself and invited three new mothers with their infants into her carriage, so they would survive the trip.

She bought a big sack of bread whenever we came to a big bakery and hung the sack from the side of the carriage. We had a camp kitchen, a “Gulaschkanone,” to cook huge quantities of soup. We had plenty to eat then.

Once we came to an abandoned town with a castle and people had fled, leaving everything behind. We slept anywhere we wanted, even in the castle. The houses were full of food, because these people had also fled. But after three weeks, we heard the Russian guns.

Eventually, we arrived in Schleswig-Holstein. The countess’ brother had made arrangements for us, but the Nazis were still in charge, so they assigned people to various houses in the village as they saw fit. It was awkward and unpleasant.

We lived over a bakery in a tiny room with five other people. Baked goods were rationed, so we smelled a lot more bread than we ate.

People looked at us funny because we weren’t from there. My mother and sister argued about words for years, because my mother didn’t want us to blend in. She thought we were still going “home” one day. She wanted us to fit in whenever we got there.

The Immigration Effect

Epidemiologists like to study the “immigration effect.” That’s the idea that people who stay home are systematically different from the people who don’t.

For example, people who eat lots of fruits and vegetables, little meat, and little refined sugar in their home country may have a low risk of colon cancer. If some migrate to a country with the opposite pattern, they will probably increase their risk of colon cancer compared to those who stayed at home. But because they keep some of their home country traditions, they will probably have a lower risk of colon cancer than the natives of their adopted country.

For epidemiologists, a pattern like this means the risky behavior is “modifiable,” not genetic. If you can get people to eat more fruits and vegetables, little meat, and little refined sugar, then you will probably see less colon cancer. It’s hard to change behavior, but it’s possible. It means hope.

After World War II, many, many people fled from the Eastern block into West Germany. They know what it means to be forced to rely on strangers. They know first-hand that the scarcity mentality isn’t true. Hardship can teach us generosity, if we let it.

We all wish for peace, but in the mean time, people all around me are eager to help the new arrivals feel at home. When peace comes, I think our hospitality will be gladly returned.

Spring Is Coming. Let's Not Give Up Hope.

Several years after I wrote this post, I’m still writing about these themes, trying to figure out how our world fits together, and how I can help in some small way.

If you’re looking for a family-friendly way to talk about these big topics, you might enjoy:

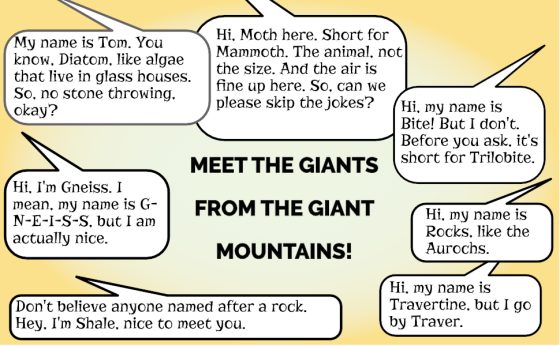

Giant Trouble: The Mystery of the Magic Beans is about welcoming visitors from the Giant Kingdom, the trouble it causes, and the young prince who tries to bring everyone together with the only weapons he has: comic strips, chapati, and chopped onions!

For ages 9 to 12.